Yolol Parsing In Which A Parser Is Born

TL;DR

The first stage of compiling a language is parsing it.

Compiler Series

This article is the second in a series on how to build a compiler for a simple language into CIL.

What Is Parsing

A parser turns a list of characters in a human readable form, such as 1+2*3/4, into a machine readable form (an Abstract Syntax Tree).

The syntax for a language is often defined in Extended Backus Naur Form which is simply a list of rules and which other rules can come after that one. For example an ENBF for a decimal number might look like this:

# 'x' means match the single character "x"

# [x] means `x` is optional

# x,y means `x` followed by `y`

# {x} means `x` can be repeated 0 or more times

number = [ '-' ]

, digit

, { digit }

, [ '.', digit, { digit } ];

# x|y means `x` or `y`

digit = '0' | '1' | '2' | '3' | '4' | '5' | '6' | '7' | '8' | '9';

This simple grammar defines two rules: number and digit. This grammar matches string like these:

"1":digit"-2":[ '-' ], digit"12":digit, { digit }"21.4":digit, { digit }, [ '.', digit ]

But does not match string like these:

"":digitis required"-":digitis required"a":digitmust be 0..9"9.":digitis required after'.'

When the parser fails to match can be almost as important as when it does match! You’ll want to take these syntax errors and give them to the user in a useful way. For example:

"9."

^ Expected `digit` but encountered end-of-file

Abstract Syntax Trees

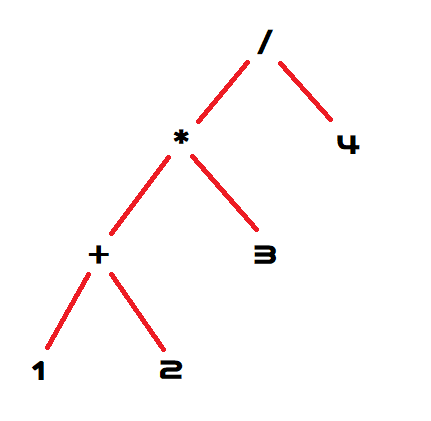

I mentioned above that a parser usually outputs an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). An AST is a tree representation of the code.

In this example you can see that the expression 1+2*3/4 has been broken down into a tree of nodes which each represent one part of the expression. Exactly how you represent this depends on your language - in a language like Rust you’d use an enum with a variant for each expression type. Unfortunately C# doesn’t have discriminated unions (yet?) so it’s a little less convenient:

class Number : IExpression {

public double Value { get; }

public Number(double value) {

Value = value;

}

}

class Divide : BinaryExpression {

public Divide(IExpression l, IExpression r) : base(l, r) {}

}

abstract class BinaryExpression : IExpression {

public IExpression Left { get; }

public IExpression Right { get; }

public BinaryExpression(IExpression l, IExpression r) {

Left = l;

Right = r;

}

}

interface IExpression { }

This is a very simple AST, a real world one might contain some extra information. For example my Yolol AST classes have an IsConstant property which indicates if the node represents a constant value (3+4 is constant because both 3 and 4 are constants but 3+n is not constant because n is a non-constant variable).

Parsing Options

todo: PEG/LALR/etc

Do You Really Need A Parser?

So now that I’ve spent all this time explaining what parsers are… do you actually need one? If you want to write your own completely original language as a string the answer is simple: yes. So for Yolol I definitely need it.

However, if you’re trying to write a Domain Specific Language (DSL) which is embedded in another language you might not need one at all.

The simplest option is to skip the parser and directly construct the AST. This can be quite ugly, but it completely avoids all of the difficulties associated with parsing and pretty much eliminates the possibility of a “syntax error” (there’s no syntax!).

// a = (17.3 + a) * 4

let ast = Assign(

Identifier("a"),

Multiply(

Add(

Number(17.3f),

Identifier("a")

),

Number(4),

)

)

Another option may be to derive the AST from some other structure that you already have. For example the JIL library accelerates JSON serialisation by compiling a method on-the-fly specifically for the type of JSON you’re handling. It doesn’t need to build an AST, instead it can inspect the AST of the JSON and convert that.

{

IntVal = 1,

StringVal = "hello world",

}

Could be walked over and turned into an AST automatically:

let ast = JSON(

Field<int>("IntVal"),

Field<string>("StringVal")

)

Finally in C# there’s a fairly unique third option: Expression Trees. Expression trees allow you to write standard C# but instead of that code being compiled into executable code the AST from the C# parser is embedded directly into your program, so you can inspect it at runtime. This basically allows you to directly use the C# parser as your own parser, as long as you want your syntax to look like C#.