Pathfinding In Which The AStar Pathfinding Algorithm Is Revealed To Be Both Very Complex And Very Simple

TL;DR

A* pathfinding is pretty conceptually simple, but can be quite complex to implement.

What Is Pathfinding?

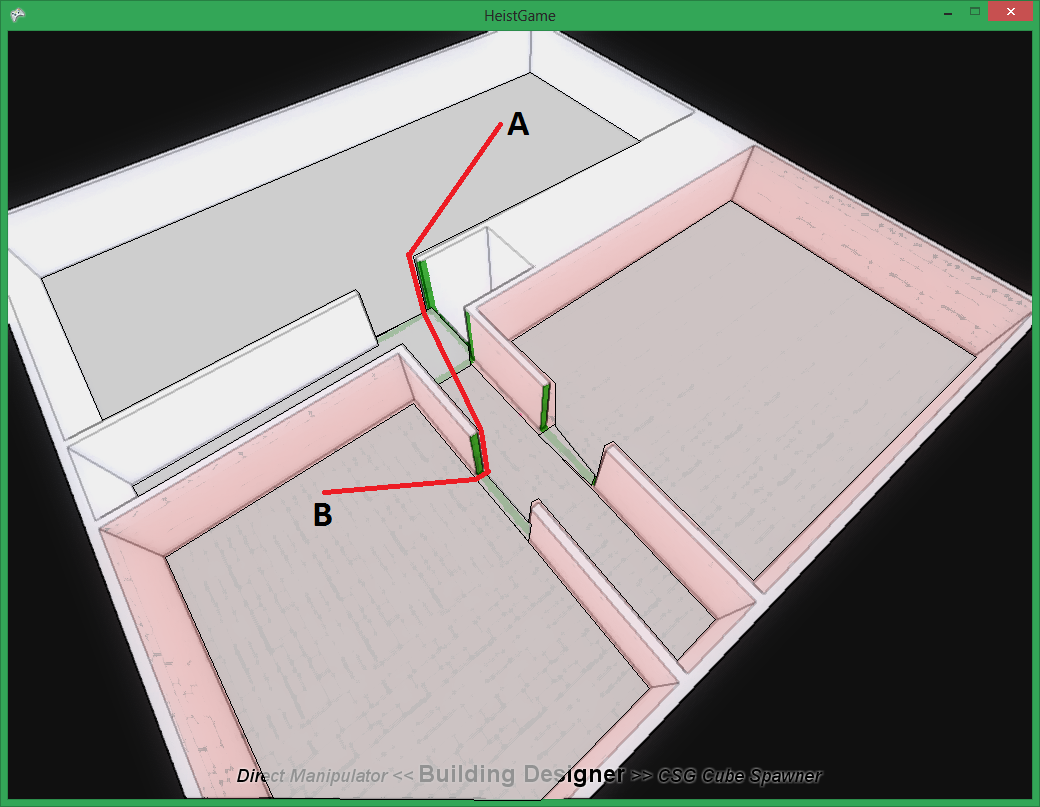

Pathfinding is really quite a descriptive name - How does someone get from A to B? Obviously they need to find a path! Of course this is a bit of an oversimplification - you can’t simply dump an AI character into a game and say “Go to this point”, you need to give them some understanding of the shape of the world (e.g. you can’t walk through walls). In games the world is usually represented with a “navigation mesh”, for example:

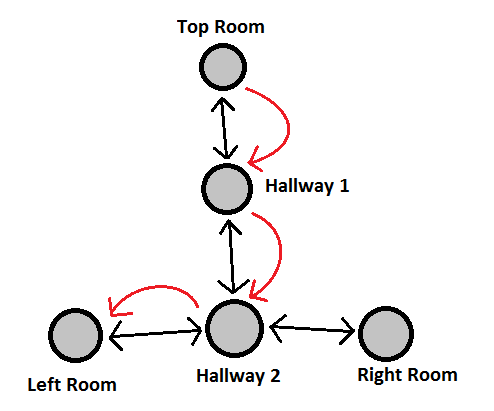

The grey areas are convex polygons which make up the navigation mesh, AI’s “know” that they can only walk over areas the mesh covers. Hence, an AI getting from A to B would have to follow something like the red line. Let’s simplify the problem a little bit by removing all the geometric aspects of it. This would look a little like this:

Again, the grey blobs are representations of where the AI can walk and the red arrows indicate the solution to the question of how to get from A (contained within “Top Room”) to B (contained within “Left Room”). Formally, the grey blobs are “vertices”, the black arrows are “edges” and a load of vertices and edges together form a “graph”. Pathfinding, in this abstract representation, is simply the question of which edges should be followed to get from one vertex to another.

Brute Force

The obvious way to find a path is with brute force, let’s see how that would work.

- Mark current vertex as visited

- Add all connected vertices (which are not marked as visited) to a “to do” list

- Set current vertex to be a vertex off the “to do” list

- If current vertex == destination, we’re done! Exit

- Goto 1

Basically, keep exploring every single possible path until you find the destination. I think it should be pretty obvious why this is a dreadful way to solve the problem, to solve even a relatively small problem you’ll end up visiting very large parts of the graph.

Best First

The problem with the previous example was it considered every possibility equal, so it would explore every single possibility on the way to the destination with equal priority. Think about this from a more human perspective - if you were tracing a route on a map you wouldn’t trace every single little side road on the way, instead you’d take the largest roads until you were nearly at the destination and then if that didn’t get you all the way there start backtracking and trying smaller roads. Essentially, a human would try the best possibility first and then backtrack if this fails. This is the essence of A* search - the search will check out the nodes cloest the destination first:

- Mark the current vertex as visited

- Add all connected vertices (which are not marked as visited) to a “to do” list

- Sort the “to do” list by (Distance so far + guess of distance remaining)

- Set current vertex to the vertex which is guessed to e closest to the destination

- If current vertex == destination, we’re done! Exit

- Goto 1

The only difference is that, when picking which vertex to check next, A* picks the one which is probably (according to some guesstimate of distance) closest to the destination. Interestingly it turns out that so long as the guesstimate of remaining distance is always less-than-ore-equal-to the actual distance you’re guaranteed to get the optimal path (even though you didn’t check every possibility). Here’s a handy fact: The distance “as the crow flies” between two points is always less than or equal to the path between those points. So if you’re doing pathfinding in 3D space you can just use A* - with the euclidean distance as your guesstimate - and you’re done.

Fiddly Details

As with any efficient implementation of an algorithm there are fiddly little details that make A* harder to implemented than you might expect. Let’s think about the things that algorithm I described above does:

- Mark vertices as visited

- Find the vertex on the to do list with the smallest guessed distance

- Guess the distance from A to B

Mark Vertices As Visited

The obvious way to do this is for vertices to have a field “visited” which you simply set to true. If you do this then checking if a vertex is visited is a dead simple boolean conditional (can’t get much more optimised than that). The problem is now every pathfind is modifying your vertices, when you complete your pathfind you have to go back over all the vertices and mark them as unvisited and running multiple pathfinds in multiple threads becomes rather difficult. A better approach is to keep a set of visited vertices - checking if a vertex is visited just involves checking if it’s in that set, for a hashset this is an O(1) operation - i.e. pretty cheap.

Pretty cheap wasn’t quite cheap enough for me. Instead of a hashset I use a Bloom Filter which is faster than a hashset (and also uses significantly less memory) but has the possibility of false positives, i.e. sometimes when checking if a vertex is visited a bloom filter will decide it has been visited even though it hasn’t really. If that happens the pathfinder might generate different (less optimal) route. I decided this wasn’t really much of a problem, the chance of false positives is very low and so it will only happen very occasionally, and since we’re trying to simulate human behaviour we don’t want the paths to be perfectly optimal all the time! The one problem with bloom filters than had me worried was that as the number of items in the set grows so does the probability of a false positive - meaning that for a very long pathfind the chance of multiple false positives could grow to a near certainty! To counter this I actually use a Scalable Bloom Filter, which maintains a certain error rate no matter how many items are in it.

Find The Best Vertex

The obvious way to do this is to keep the todo list as a literal list and then simply sort it as items are added. This is a very expensive way to do this because a sort operation sorts the entire list, but all you want to know is the smallest item. A better way to get the smallest item in a set is to use a Heap. A heap allows you to add an item and to remove the smallest item added so far. It does this far more efficiently than sorting the entire thing every time.

Estimate The Distance Remaining

As I mentioned above, the distance estimate must be less than or equal to the actual distance remaining - this means that directly measuring the distance as the crow flies is a good guess for A*. Of course doing so is simple high school maths:

Distance(A, B) = Square Root((A.x - B.x)2 + (A.x - B.y)2)

That’s that sorted then. Simple!

Naturally my implementation isn’t really that simple. Although for a perfectly optimal path the heurustic must always be less than or equal to the actual length if the heuristic slightly violates this and overestimates the pathfinder can sometimes find a (less optimal) path slightly more quickly. Wikipedia calls this Weighted A*. The essence is that if, in the worst case, your heuristic is N times as long as the actual distance then, in the worst case, the pathfinder will find a path N times as long as the best path but it will do so more quickly than if you’d forced it to find the best path. I threw this into my implementation as soon as I found out about it, it’s dead simple to implement (just multiply by a number) and if you decide you need an optimal path then you can just use 1 as the multipler!

Path Following

The elephant in the room is that this A* simply tells us which edges in our abstract graph to follow… but what then? How to actually follow the path is a separate problem involving steering behaviours and tying into the animation system to move feet properly (perhaps with inverse kinematics). This is a very different problem which I shall come back to soontm.