Procedural Generation For Dummies: Lot Subdivision In Which Space Is Made

Procedural City Generation For Dummies Series

- Procedural Generation For Dummies: Building Footprints

- Procedural Generation For Dummies: Half Edge Geometry

- Procedural Generation For Dummies: Galaxy Generation

- Procedural Generation For Dummies: Lot Subdivision

- Procedural Generation For Dummies

- Procedural Generation For Dummies: Road Generation

My game, Heist, is a cooperative stealth game set in a procedurally generated city. This series of blog posts is an introduction to my approach for rapidly generating entire cities. If you’re interested in following the series as it’s released you can follow me on Twitter, Reddit or Subscribe to my RSS feed

A lot of the code for my game is open source - the code applicable to this article can be found here. Unfortunately it has some closed source dependencies which means you won’t be able to compile it (I hope to fix that soon) but at least you can read along (and criticise my code).

Lot Subdivision

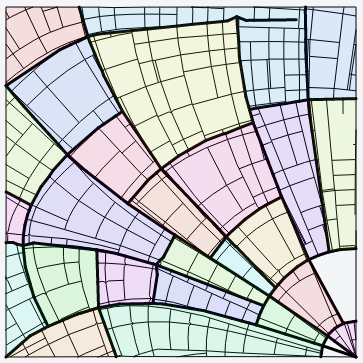

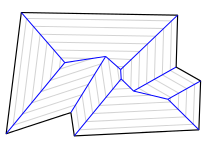

After road generation has finished it will have generated a road map which will look something like this:

The next stage of procedural city generation is to take each area surrounded by roads, called a parcel, and decide where to place buildings in this area. The spaces buildings are placed into are called “lots”.

I have come up with two different lot generation algorithms: OBB Parcelling and Straight Skeleton Subdivision; both based on this paper. So far I have only implemented OBB parcelling.

OBB Parcelling

OBB (Object Aligned Bounding Box) Parcelling is a method for recursively dividing a space into roughly cuboid parcels. It is best when the initial space is nearly cuboid, for example in a Manhattan style city.

The algorithm is quite simple:

function obb_subdivide(space) {

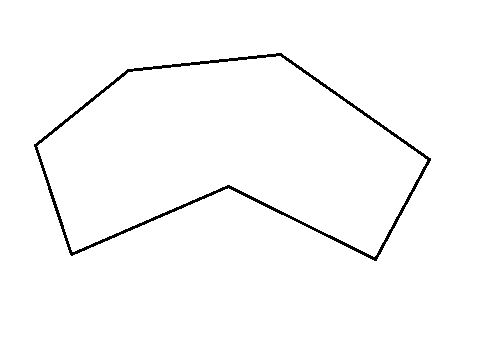

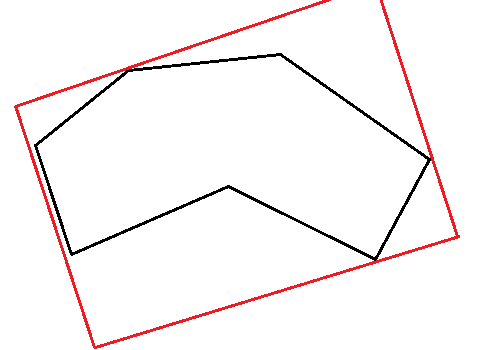

// 1. Fit an Object Aligned Bounding Box around the space

let obb = fit(space);

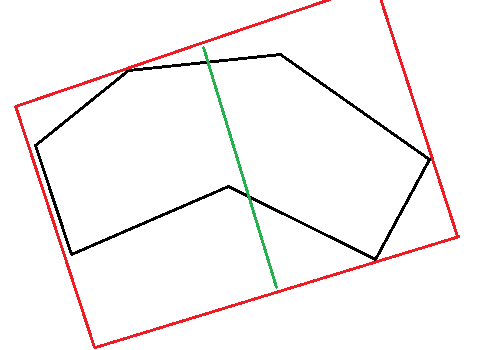

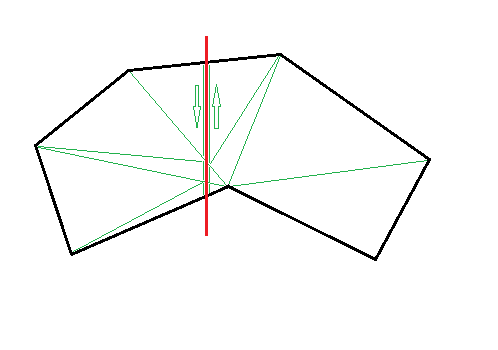

// 2. Slice the space along the shorter axis of the OBB

let parts = slice(obb.shorterAxis, space);

// 3. Check validity of all children, terminate if any are not valid

// This is the base case

if (parts.Any(IsNotValid))

return space;

// 4. Recursively apply this algorithm to all parts

for (part in parts)

return obb_subdivide(part);

}

The first step is to fit an object aligned bounding box to the space. My approach to this is basic brute force; since the OBB must be aligned to one of the edges of the space, I simply generate every possibility (equal to the number of edges) and then pick the smallest one. Generating a box along an edge simply requires projecting all the points of the shape onto the axis so the total cost ends up being proportional to Edges * Points, which is equivalent to Edges ^ 2. Normally it’s best to avoid algorithms with an exponential cost but in this case it’s ok - the number of edges in a space is unlikely to be high enough for this to become a problem.

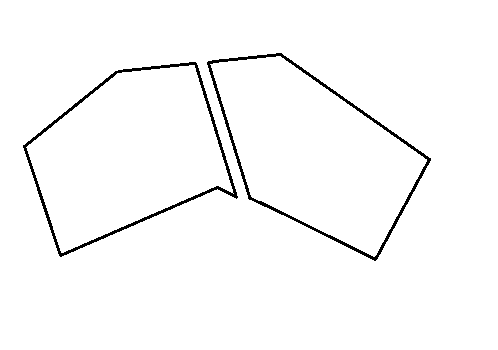

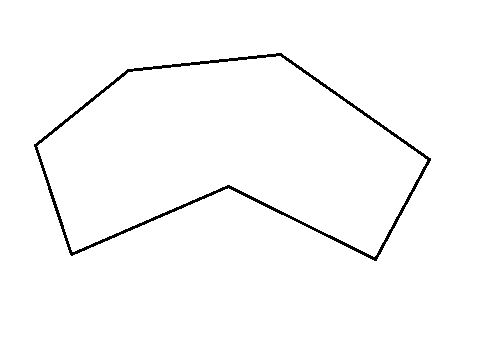

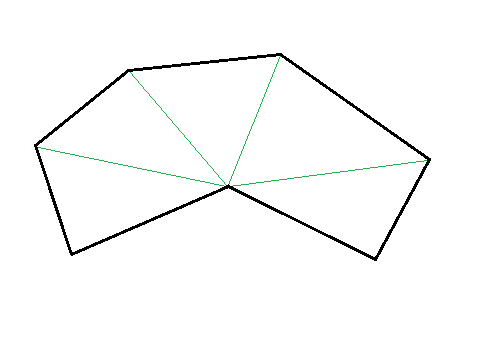

Now that we have an OBB surrounding the space the second step is to split the space in half. This is done by cutting the shape along the shorter axis of the bounding box. There are multiple techniques to slice a 2D shape, I decided to come up with my own (based on the code I had available). My technique is based on generating the Delaunay triangulation of the shape (using the Poly2Tri library). Slicing a triangle is trivial - you just need some careful handling for the slice line and triangle edge being perfectly co-linear. Once the triangles are sliced it’s a simple matter of walking all the directed edges and reconstructing the result (I may do a more in depth post on this, if people are interested).

After slicing we have generated two new shapes and we can now apply the same algorithm again, recursively. The only thing left to establish is when to stop, i.e. the base case. My implementation supports four rules, as soon as any rule is violated by a child shape then recursion is stopped.

Area

The most obvious rule is the area rule. This sets a lower limit on the area any lot may be. Recursion stops if any slice line generates a lot below this limit.

Access

This rule governs things parcels have an edge connecting to. The initial edges of a space have “resources” attached to them (e.g. road access), recursion stops if any generated lot does not have access to a required resource.

Aspect Ratio

This rule governs the aspect ratio of a lot (length / width). This sets an upper limit of the aspect ratio of any lot. Recursion stops if any generated lot exceeds this limit.

Frontage

This is a specialisation of the access rule which measures how much access a lot has to a resource. This sets a lower limit on the length of edge next to a given resource, recursion stops is any lot of generated with smaller frontage.

All of these rules have a probability associated with them. This is the chance that recursion will not terminate even if the rule is violated - for example you could have a block setup like this:

- Area { Min: 100, Chance: 0 }

- Frontage: { Min: 5, Chance: 0.25 }

- AspectRatio { Max: 1.5, Chance: 0.25 }

- AspectRatio { Max: 2.5, Chance: 0 }

In this example we have two hard rules which will not be violated (area and aspect ratio 2.5) as well as two rules with a 25% chance of violation (frontage and aspect ratio 1.5). Since the rules are evaluated for every new subdivision the chance of a large rule violation becomes increasingly unlikely with every slice (25%, 6.25%, 1.56%, 0.39% and so on).

Straight Skeleton Subdividing

As mentioned above I have not yet implemented this algorithm so I can’t go into a lot of detail about the implementation.

Straight Skeleton Subdividing (SSS) is an approach to generate lots in one single step. It works only on long thin parcels - quality of the generated lots drops as the initial parcel approaches a square shape - it’s best used for suburbs with long winding roads. The straight skeleton of a shape is a line which is what you’d end up with if you collapsed a shape inwards at an equal rate from all points. This is incredibly complicated to generate, in fact I gave up attempting to implement it myself in C# and ended up writing a C# wrapper around CGAL to access the methods I needed. Wikipedia puts the runtime cost at something like O(N^3 log N), which is pretty scary!

Once you have the straight skeleton, lots can be placed along the edges connecting between the external points and the skeleton. This leaves annoying triangles at the ends which need to be somehow detected and removed. Requiring these kind of heuristics is part of the reason I haven’t implemented this yet.

What’s Next?

In this post I’ve covered two algorithms for how to generate sensibly shaped building lots, as well as implementation details for one of them. Next time we’ll look at the complex relationships which are tracked when deciding what buildings to place in each lot.